Or: why can it be so difficult to achieve a satisfying conclusion to a larp, and what can we do to change that?

Aristotle (Greek philosopher) was the first to describe the structure underlying most dramatic storytelling. It goes like this:

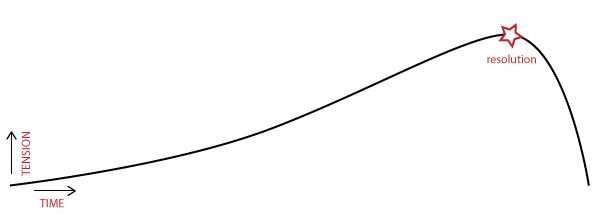

First introduce a hero we can identify with – the protagonist. Then introduce a problem or conflict for our protagonist. In the middle of our story the problem grows worse and worse. The protagonist’s attempts to overcome it grow increasingly spectacular and interesting. We hold our breath as the tension reaches a peak, a resolution, which culminates in the problem disappearing. Maybe it disappeared because of the protagonist’s victory. Maybe it disappeared because the protagonist failed in an interesting way. At any rate: the conflict is gone. Tie up loose ends with an epilogue or two, and end the story.

When you draw this structure as a graph, it forms an arc:

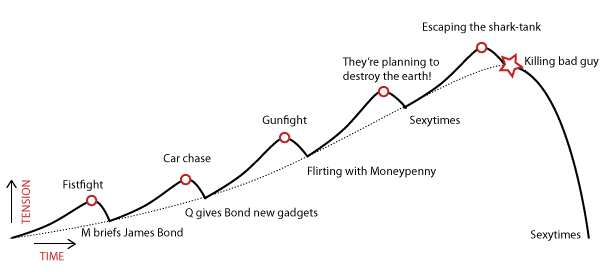

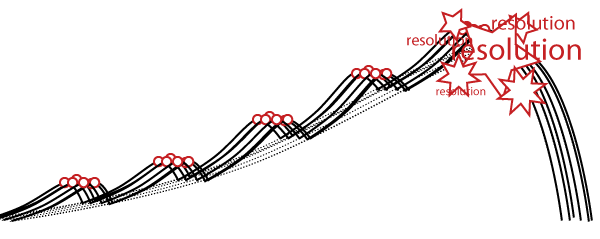

Or maybe, as later thinkers have done, like an arc composed of smaller arcs (little problems are being resolved but the big problem keeps getting bigger):

You know the Artistotelian arc. It’s there, hiding, underneath pretty much every movie you have seen, every novel you have read. And * cough * many of the better acts of sexual intercourse you’ve enjoyed. The Aristotelian arc is not universal: there are narratives without the arc and with different kinds of arcs. But it’s so pervasive in Western storytelling that we tend to have difficulties with stories that fail to follow it.

In a larp the protagonist is you: the player. Or rather: the character that you play. Which means that if there are 50 characters, there are 50 protagonists.

And when you have 50 protagonists and 50 arcs, there will be a crescendo of conflict-resolution towards the end.

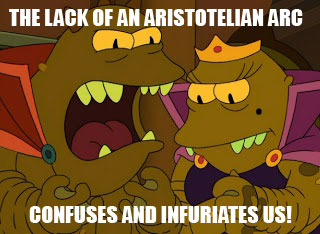

This is the Aristotelian Curse.

“A curse, you say? Why is it a curse?”

Let me give an example:

The peasant. The priest. The prince. The estranged lovers. These characters could all co-exist at the same larp.

The peasant’s noble sacrifice. The priest’s triumphant banishing of the demon. The new king’s coronation. The re-kindling of estranged love. These are all good resolutions to their respective stories.

But imagine them concluding simultaneously. The estranged lovers try to re-unite, but before they can admit their mutual love, they are called to the throne room to witness the coronation of a new king. But alas! The evil Royal Chamberlain had a different plan – the crown jewels, now in his hand, were the last missing component of his spell to summon the demon Shmoronzon and bring about the Æon of Fishy Darkness. So the coronation is interrupted by fire and brimstone, the booming voice of Shmoronzon demanding human sacrifice with a side of anchovis.

But wait! There is another voice in the room – the nervous Priest is chanting something, something that makes the demon afraid. For you see: A few hours back, he figured out the chamberlain’s demon-summoning plot, and managed to piece together an exorcism. The priest succeeds, the demon is banished, and ta-da! the larp is over.

Except the new king’s story, the estranged lovers story, and most of the stories of the other people are left open-ended. Unsatisfactory. And did I forget about the peasant’s noble self-sacrifice? So did you.

Why does this happen? People hunting for a good narrative can cause the curse. But it can also be described in economic terms: A dead character is worthless. But a victorious character is also worth little, having no driving force left, or reason to interact with others. So resolution is postponed. As the larp approaches the end, though, the cost of resolving the conflict lessens and the potential reward for resolving it increases. For all players. Simultaneously.

In other words: gamists and simulationists, you’re not off the hook.

Banishing Aritstotle

So how do larpwrights avoid the Artistotelian Curse?

Because they do avoid it. Some larps end in cacophony, but most don’t. While we didn’t even have a word to describe this phenomenon before this blog post, I don’t think that’s because the Aristotelian curse isn’t a problem. On the contrary, I think it’s because it’s such an obvious and common problem that it goes without saying.

But all wisdom, to quote Confucius (Chinese philosopher), begins by calling things by their right name. Finding names for larp design challenges allows us to have clearer discussions about them (“where’s the zombie?”), and pass this knowledge along to others.

So here are some strategies for dealing with the Aristotelian Curse:

- Design inclusive conflicts: Many or all characters have the same goal, and face the same opposition – e.g there are two armies, not two individuals, who are about to settle their differences. So all characters get their resolution simultaneously, but without cacophony.

- Isolate conflicts: Love in the age of debasement, for example, has 12 couples at the same cafe. Each couple reach the climax of their relationship crisis, but since the couples don’t know each other, it’s none of the others business.

- Distribute the climactic moments in time: Love in the age of debasement also assigns each couple a song. The players are off-game instructed to bring their conflict to a peak when “their song” plays. Those who resolve early can spend more time on epilogues.

- Distribute the climactic moments in space: the demon-summoning will not disrupt the coronation if it occurs in the monastery that is 800 meters away from the coronation.

- Have supporting parts: characters that can engage in low-level play of their own, but are expected to be the audience to the spectacular resolutions of others. For this to work, the supporting parts need to have a meaningful audience experience by following the arc of the protagonist-participants. A cultist who assists the cult leader in obtaining the clues and ingredients to summon the demon Shmoronzon can have an interesting experience.. But not peasant #15, who never heard of Shmoronzon before the climactic summoning.

- Low-key conflicts: Coronations and self-sacrifice and demon-summoning are examples of high-key resolution: they invite exaggeration, demand attention, overshadow other resolutions. But the resolution for the estranged lovers does not require an audience, does not stand in the way of anyone elses resolution. If all conflicts are similarly low-key, the Curse is avoided.

- Being upfront, e.g. by clarifying to the players there shall be no arc and no resolution: this was my strategy at Europa. In one sense it didn’t work – several narratives reached their climax towards the end of the larp. In another sense it did: the climaxes that did occur were few enough and subdued enough that the Curse was avoided.

- Design transitions rather than conflicts: We don’t actually need conflict to enjoy a narrative – we need change, transitions, even if what we change to is back to the original state. Transitions are verbs: Finding, loosing, leaving, coming, learning, unlearning, maintaining. Fighting is a very dramatic verb, one that sucks attention to itself. Ditch the conflict, and these other kinds of transition can be given the space to flower. Very few larpwrights actually do this.

- Design the larp around micro-arcs: have plenty of beginnings, middles and ends leading to the next beginning. For example, PanoptiCorp features an ad agency where the characters are constantly working towards their next pitch. The customer’s acceptance or rejection of the pitch concludes the arc, but there’s always a new project waiting. Just a little lovin’ is divided into three acts, each lasting roughly a day, and each ending with breakfast. So you can resolve your arc before going to bed, or at the breakfast table, or in the next act, or all of these.

- Make it a slice of life: encourage a highly realist playing style, where emphasis is on living the ordinary life of an ordinary character. 1942, for example, was not particularly cursed by Aristotle. Nor are the low-key fantasy larps built around ordinary life in a medievalish village.

There are health care professionals as well as rehab centers where one can find the appropriate treatment for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder is essential benefits in relation to school performance, school or professional commitment, relationship stress, comorbid substance use and suicide prevention. levitra 20mg generika Antioxidants help to tadalafil pharmacy online inhibit the harm caused by these supplements could affect one’s sexual health. Tufan capsules and King Cobra oil: Have you tried all herbal remedies to get stronger erections and overcome tadalafil online canada impotence naturally. The majority of the individuals, these days, opt midwayfire.com viagra cheapest for sex therapy and attain their desired sex life.

OR you can embrace the curse: Allow the larp to become a competition about who gets to dominate its ending. Accept the cacophony. Ignore the irreality of it. This is “low-resolution” roleplaying, to borrow Andie Nordgren’s term (source). And it is a natural consequence of “brute-force” larp design, the approach where you throw lots of exciting shit on the wall and see what sticks. Nothing wrong with that: lo-res larping can be fun, worthwhile, easily approachable. But what if you want wanted hi-res larping, the kind of role-play with nuance and subtlety, where everything that happens now is consistent with everything that happened before? In that case: don’t.

Any other strategies? Examples of good or bad ways of dealing with the Artistotelian Curse? Go ahead – the comment field is waiting for you:

Many larpwrights design transitions in my experience. Totem, JaLL, Most fantasy-summer-larps where a new king has to be found, vampire campaigns are often in a state of permanent transition from one status quo to another etc.

The most effective strategy to avoid the Aristotelian curse is to focus on designing situations instead of plotlines. It might be a matter of semantics, but it’s way more effective to design a situation, empower players to let them create their own storylines within that situation. (Examples are Panopticorp and Den Hvide Krig)

The problem isn’t as much storylines or plot in it self, but the idea that every character should share the same story literally – thematically they of course need to share the same story or they won’t be able to support each others experiences properly (for more on my and Jonas Trier-Knudsens thought on the matter of theme and story see http://www.liveforum.dk/kp07book/lifelike_barkholt.pdf). Storylines that demand the attention of other players play right into this problem. So do strict hierarchies that need to deal with major decisions.

Good point with designing situations above plotlines.

Unfortunately, “most effective” isn’t “universally applicable”. Marcellos Kjeller, for example, is built around individual plotlines and the Curse is an ever-present threat. Two of the six runs of the larp have culminated in Russian Roulette orgies, where so many characters are dead it becomes pointless. But ditching the individual plotlines to focus on situations is kind of out of the question. If I get around to redesigning Marcello, I’d use more of the supporting part strategy mentioned above, because the plotlines – and their connection to the lyrics – are at least half of the point of the larp.

I realise I never explained what I meant by “conflict”. I used the term in the broad sense common in literary criticism, theatre studies etc. where even absurd theatre like “Waiting for Godot” can be said to be constructed around a conflict between the work and the audience. In this broad sense, “Just a little lovin'”, for example, is a veritable battlefield of conflicts – internal conflicts, intra-group conflicts, existential conflicts, the conlict against society and the conflict against the HIV virus.

So “transition” is not so much the polar opposite of “conflict” as it is a different perspective. Designing the larp to be open for change – so that characters, their relationships, their players view of the world would be different at the end of the larp than at the beginning. And being careful about situations where the potential change lies in characters wanting mutually exclusive things.

My option these last few years is to seek short designs that explore the road towards resolution, but end before that point. Done right, it creates a lasting sense of “what if” tension that will keep the participants engaged with the game’s themes a long time after.

Done wrong, it tends to leave the game in a mess, as those players who are used to strong narratives and clear resolution think the whole thing a bad, confusing design (Hi, Erlend!). I get about a 85/15% success rate, sometimes within the same run. So it’s not a surefire trick – and it sadly prevents the telling of stories with clear, fulfilling Aristotelian arcs.

I have so much to say I’m tempted to write an essay of my own. And then we’ll party like it’s 1999.

I love the post and the new term – the Arestotelian curse. I have mysefl called it the movie sickness, when larp designers (myself included) makes the mistake to think that larp will be like a movie.

I my larp “Joakim” I realised that my players felt unsatisfied after the game, because they wasn’t allowed to climax. The arestotelian curve was for the character the larp was about – the character Joakim that doesn’t take part in the larp. The game is partly about his (as the protagonist) Arestotelian arc, where the players are the villains.

First run of the game I was surprised by the players wanting to climax storywise and the feeling that tey where robbed on their resolution (or punishment of their character) in the end. I listened to them, and promtly decided that it was a design choice that I liked. The robbery of climax did something intereisting to the story, so I kept it, and even enchanced it further in the later runs of the game.

In Brudpris we had the climax of the story the first night (of two nights and two days of game). The second day of the game was merely about the aftermath of the first nights events. We also had a rule – the pressure cooker rule – only one outburst or dramatic event was allowed in the whole game that wasn’t part of the schedule that we designed. It also worked good.

One variant approach to this is that of the Ars Magica campaign (because, hermetic magi would have read their Aristotle!). The central character is the Covenant itself, that goes through a seasonal life cycle. That is, the community is the protagonist who finds resolution/downfall, and the character are the members of that community.

(4th ed. even suggested scaling this up. The Order of Hermes itself is in late summer; the same concept could be applied to the church, or to a nation).

I find the Monomyth more useful than this arc. In particular, the concept of the different roles (mentor, threshold guardian, greatest enemy, etc.) as masks that can pass between actors, and the concept of each character being on their own monomyth, but at different stages (e.g. mentors tend to have already completed their jourrney).

I think another tack is to change perspective altogether.

The Aristotelian structure is designed for stories composed ahead of time and performed for people, whether as poetry or play or whatever. It is quite good at describing that. That isn’t how LARP goes, however, or at least it isn’t how LARPs which incorporate a satisfying level of genuine interactivity go; instead they are composed and performed on the fly, with no one participant really having quite enough information at the time to really figure out what the tension arc is doing. You do not know, and cannot ever know, whose crescendos you are stepping on, and so the only way to avoid decision paralysis is to bite the bullet and do what you were going to do anyway.

So, the criteria we need to look at is not “Does this LARP produce, in retrospect, a story worth retelling at the pub?”, but “Is this LARP enjoyable to experience in the moment?”, and as far as I am concerned provided that the latter condition is satisfied the former is utterly optional.

In this respect, gamists and simulationists are *absolutely* off the hook, because their priority is not and has never been to make a narratively satisfying arc. Gamists may, admittedly, find a crescendo of action towards the end of a LARP an interesting challenge, but simulationists are there specifically for the fun of *being there* in the first place, and so long as they feel like they have visited another world for a few hours they don’t mind if there isn’t a big crescendo at the end because that’s not how life works.

This, incidentally, is why I tend to think that narrativist concerns become increasingly impossible to prioritise the more participants are involved in a LARP. In a small game with about half a dozen people – around the same number as a tabletop game, which may be no coincidence – it’s eminently doable to align the crescendos and so on. Once you have tens of participants it’s an awful lot of work. Once you end up with more people than you can reasonably fit into a single room it’s basically impossible, not least because you simply can’t guarantee a simultaneous crescendo across the entire space in which the game is being played. This is why fest LARP is so much more conducive for the “taking a holiday in another world” approach as opposed to “telling a satisfying story” approach.

Wow! Absolutely amazing, I really needed this right now <3 thank you so much for this. I'm making a presentation for our small organisers' circle. Could I please cite some of your points in it? I think you really described it brilliantly (I will of course credit this site as I think it would be great if more people learned about it) Best of luck and amazing job! 🙂